I can’t recall how exactly we located our new lodgings in Taghit. As I mentioned before, I was happy to entrust the logistics to the others. Apparently Mustaffa, the restaurant owner, had arranged things. We were to stay in the house of a local man a few kilometres north of the town. Like a typical desert inhabitant he had a dark complexion. He was slight of stature and it was hard to gauge from his neutral expression how pleased he was having us inhabit his home. I was unsure how much we were paying but Sofian assured me that the price was negotiated beforehand. The house was a modern structure, one of half a dozen or so on either side of a dusty street beyond which was a large expanse of dusty flat-land and the main road from town. He ushered us into a medium-sized living room where we would be sleeping. It had a small box TV set, several sofas accommodating a pile of cushions and blankets and a couple of mattresses on the floor in between. Against one wall was a picture of a young Muslim girl in earnest supplication before a picture of a mosque and minarets, a field of flowers and a night sky with stars and a crescent moon above. I saw this picture in a number of different homes and buildings on our travels. It obviously struck a chord with Algerians.

I was under the impression that we would be sharing the house with its occupant but apparently he was staying elsewhere and we would have the place to ourselves. Besides the living room there was a kitchen with a fridge and gas oven, a bathroom, toilet and a master bedroom. Not surprisingly there was no running water but a large plastic basin was filled in the bathroom and several plastic jugs and mugs were at hand. The furnishings were mostly cheap and more than likely Chinese but the place was tidy and clean and more than adequate for our needs.

I don’t know where the day went but by the time we had made it back to town it was late afternoon. Incidentally, it was the last day of the calendar year and that would explain the multitude of cars and pedestrians that had converged on the little town. There was only one main road bisecting the town and it was badly congested at this time. Numerous cars with northern number plates joined the queues mingling with buses and taxis at the main terminus. A couple of gendarmes stood on a street corner keeping an eye on proceedings but no-one seemed to be paying them much attention. This was the real hub of the town and where everything and everyone would converge: traders selling coloured bolts of cloth for shesh; fruit sellers; curio vendors; taxi-drivers and their cabs; buses and their touts; and street-side hawkers like a man selling bottles of camels’ milk sitting on a street corner pavement. Sofian told me that he wanted to buy one for his mother to help alleviate a health issue she was suffering from.

We made our way to a take-away to one side of the terminus, a place we would revisit on several occasions, advertising pizza and ‘fasfood.’ In reality it was nothing like a McDonald’s. There was a large pot of seasoned mincemeat on a hot-plate, from which a man in T-shirt with ‘Algeria’ written on it in bold letters was ladling dollops into hunks of open baguette. Jamel and Oussama each opted for one of these whilst Gilmour recommended to me that we buy an Algerian speciality called m’hajip. The best I can liken it to is a pancake with spicy filling. With our food securely wrapped in foil we headed back across the road towards the dunes on the other side. Much like Béni Abbès the dunes impinge right upon the edge of the town with only a relatively short stretch of flat ground separating the buildings from the mass of sand. Whether or not the dunes ever inundated the roads or buildings I never thought to ask, but I suspect they must do. On the flat ground there were various individuals and groups heading this way and that. Several pick-up trucks were parked randomly, its occupants somewhere above us on the sand dunes. Another arrived over-laden with youngsters, driving at full tilt before pulling up sharply at the base of a dune whilst they all leapt off laughing and shouting. From somewhere a quad bike appeared and scaled a steep-sided dune with apparent ease.

We stopped halfway up to consume our food while it was still hot and because we were all famished. The m’hajip wasn’t bad but Gilmour insisted the dish wasn’t as good as it was in his town.

“My mum’s is the best. More spicy, more flavour,” he insisted. It’s good to see that some things don’t change between cultures! Incidentally it was the last day of 2013. Watching the final sunset of the year from the top of a sand dune was obviously foremost on everyone’s mind. I was surprised by how much activity the end of the Western calendar year had generated. Sofian suggested that this was a relatively recent development and mostly only celebrated in the major cities or where the city dwellers had chosen to go at that time e.g. the desert. “Will anything be happening in Ain Oulmane?” I asked him.

“No, it won’t be a big deal,” he replied.

Still, I reckon a fair few of the local kids were enjoying the excitement. I remember Sofian talking to a couple of them near the summit. Many of them were throwing themselves down the steep slopes doing cartwheels or sliding on their backsides much like the scenes we had witnessed the evening before in Béni Abbès. There was a good reason why many people chose to walk up the edges of dunes (where they met) rather than the facing slopes; it was a lot easier going. The sand on the slopes was looser and one expended more energy on the climb up. Regardless of the conditions the climb up was a good test of fitness. Sofian and I pressed on ahead regardless of shouts from further back for us to slow down. Ahmed in particular, a fairly regular smoker, stopped frequently for breath, placing his hands on his thighs. He was the only one who regularly wore a shesh, beige in colour. He was also a bit on the portly side and by the time he reached the crest of a good few minutes behind he was well out of breath.

“C’est parce que les cigarettes,” he said with a shake of his head and a wave of his hand, his forefinger and index finger extended as if holding one of the incriminating objects. For once he wasn’t smiling. Still, it would be a glum person indeed who couldn’t see the beauty in the landscape from up there. Looking back west towards the town we had a good view in both directions of the road going both north and south and behind it the fat-topped ridge running parallel to it for miles on end. The sun was dipping low over the top of the ridge and the mix of light and shadow on the dunes was very photogenic. It was the view in the other direction that was most impressive though: a seemingly endless expanse of sand, or as Ahmed referred to it, une mer de sable (a sea of sand). I later gleaned from a tourist map in a hotel that referred to it as le Grand Erg Occidental (in English the Great Eastern Erg, an erg being a sand desert). Sofian and I contemplated climbing a neighbouring dune that was taller still and on which a sizeable crowd was gathering but the others weren’t so keen. We didn’t have the time anyway and the following photos are just a few of the many taken from our vantage point.

Once the sun had set and the temperature began to cool it was time to head back. Sofian challenged me to another race to the bottom and Jamel, aggrieved at having been left out the day before, joined in. Sofian got off to a flying start and never really looked back. Jamel was a few metres back and I brought up the tail by some distance. We walked back towards the centre of town in good spirits. The conversation turned to African politicians and we each impersonated one of our choice. I respectfully imitated the nasal voice of the very recently deceased Nelson Mandela which had my friends chuckling and Sofian did his favourite impersonation, that of the late Libyan leader Muammar Ghaddafi. Spreading his arms wide and grinning he intoned, “my beeble love me!” He explained to me that the letter ‘p’ was not part of Arabic alphabet and many Arabs pronounced it ‘b’ instead.

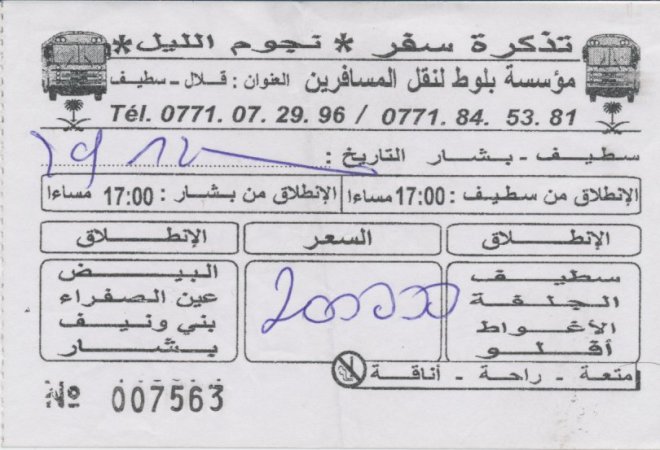

Conversation then turned towards the evening. Word had it that there was going to be a big party nearby but the price of tickets was quite dear, 4000 DN apparently. In real terms though this wasn’t much more than £20 at the street rate. I shrugged and said that I was up for it if the others were. Sofian, Gilmour and Ahmed were all keen but the other two remained quiet on the issue. When I pressed Sofian as to why they hadn’t committed he stated in diplomatic terms that they had felt it was inappropriate so far as their Islamic faith went. I wasn’t sure exactly what they anticipated but I would work it out in due course. We struggled to find a minibus heading in the direction of our accommodation but eventually we managed to jump into a chronically overcrowded bus in which I was fortunate to have a front passenger seat offered to me by the young boy touting for customers and who took the fare from them.

Back at the house Sofian took another call regarding the party. After a lengthy discussion he ended the call and shook his head looking dissatisfied. “I’m informed that the price is 6000 DN, not 4000.” It was bit annoying to be told one price and then another. As it stood I was getting short on dinars and didn’t have much in the way of hard currency on me, the remainder stashed away at Sofian’s place in Ain Oulmène. After a further phone call a compromise was reached: we could pay 4000 DN but we wouldn’t be able to eat. I shrugged and said it wouldn’t be a problem having eaten only an hour or so before. The other’s agreed. We cleaned and smartened up, ready to be collected a few minutes later. Sofian was wielding some eau de cologne and Gilmour was spraying himself with copious amounts of deodorant. “I’m gonna charm the ladies tonight,” he announced with a flourish and a grin.

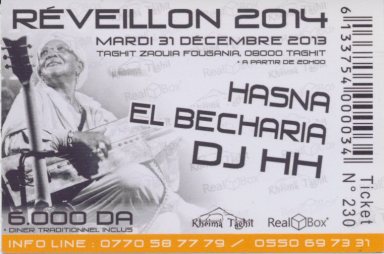

Our lift arrived at the allotted time and the driver invited me to ride up front alongside him and his friend. As it turned out the driver was also the DJ and organiser of the event. He was a relatively fair, blue-eyed Algerian from a town on the Western coast. He introduced himself as DJ double-H in English. He seemed pleased to have me aboard and we chatted about London and football, crossing the tarred road and heading off into the darkness beyond. A few minutes and a couple of bumpy turns later we arrived at our destination. I don’t know if I had impressed him with my knowledge of the UK or professing to support Liverpool rather than Manchester United, but when we arrived he declared that we would be entitled to dinner after all, even though we weren’t paying the full face value of the ticket. The main attraction was a traditional musician, Hasna El Becharai, and her group. She is pictured on the front of the ticket. Without meaning any disrespect I mistook her for Mahatma Gandhi when I initially handled the ticket!

Set up before us was a large tent off to one side and a fire blazingly brightly off to the right of it. There was much activity outside the tent where men and women in traditional garb were apparently catering for the event. Various individuals, mostly young men, stood near the fire, some chatting amongst each other, some smoking, others silently watching the ongoing preparations.

I didn’t realise it initially but the fire had a specific purpose other than providing warmth on that chilly new year’s eve. The coals from the fire were periodically scooped up with a shovel and scattered on a row of mounds in the sand nearby. Our foil-wrapped food was being slow-cooked beneath the sand.

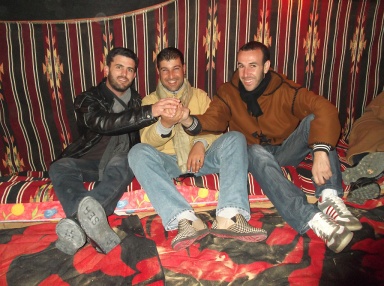

Inside the cavernous tent it was relatively quiet. As with the tent at the hostel the interior was a multitude of colours and decorative motifs. The roof material was composed of white and blue stripes (or it could have been dark green, it was hard to tell in the light). Behind the DJ’s end the backdrop was a floral-patterned rug or cloth. We chose to sit towards the back of the tent opposite the entrance side. In the opposing corner there was a small enclosure to house Hasna and her musical companions. They spent the better part of an hour there before emerging and making their way to the front and to the right of DJ HH and his sound paraphernalia. If I have to be honest I was quite impressed by the set-up: the lighting rig looked well adorned with kettle lamps; the DJ’s sound desk was attached to a cherry-red Macbook; and the speakers looked as though they could pump out a few decibels.

I had gone there without the expectation of eating, yet as the clock moved steadily through to 9 o’clock and then 10 o’clock with no sign of any food for the rest of the guests, I too found my thoughts wandering in that direction. A bottle of cola and some cutlery had been placed on a small table in front of us but had remained that way for what seemed like an age. I had gone out at some point to take a tinkle under a desert palm before ambling across to what remained of the bonfire. I saw Sofian standing nearby. There had been a bit of commotion outside the tent a few moments before. He informed me that an old women was single-handedly carrying a large pot of soup from the back when she and had slipped and spilt much of it, some on herself. Sofian was quite critical of the men supposedly involved in the event organising and catering for making an old woman do such heavy lifting. I noticed a few of these gentlemen making their presence known earlier in the tent, ushering people in. One of them was conspicuous by his rather gawky features and wonky teeth.

When the food eventually arrived sometime around 1030 we weren’t disappointed. Despite the earlier incident there seemed enough of the tasty soup to go round. This was followed by the most tender whole-chicken I think I’ve ever beheld. After two hours of charcoal-roasting the foil-wrapped chicken beneath the mounds of desert sand, it fell off the bone with little effort. To my left Gilmour fell upon it ravenously whilst I prodded the bowl of salad politely. Remembering that there were no social niceties to observe I followed suit. Within minutes there wasn’t much left beyond a dismembered carcass. We hardly needed to pick the bones so thoroughly had it been cooked. As the last of the bowls was whisked away by the attendant staff the band of six women began to play. Hasna El Becharia sat in the middle in a yellow and black headscarf and a pink and white shawl or robe. She looked the eldest by some years. The other women also wore head-scarves and garments, mostly in shades of brown, green and white. The exception was the women on the far left who wore a one-piece pink shawl.

The music was in the same style as the day before, an up-tempo beat put out by handheld rattles, shakers and a drum. Hasna played on both a traditional guitar and an electric variety whilst taking the lead vocals. The other women sang along in chorus. Hasna’s voice was rich and deep and could be quite easily mistaken for a man’s. For a while I hung back with Sofian watching from the back. Ahmed was on his feet before long, his shesh-clad head moving from side to side. I could see he was getting into the groove of things. Soon Gilmour was dancing next to him and singing enthusiastically. Unfortunately a large audience had now gathered in front of the band and I regretted that we hadn’t sat closer forward. However, after an intermission when everyone dispersed I managed to secure a position right in front of the artists next to an elderly woman in a wheelchair. Her husband proceeded to record the entire performance on a handheld camcorder. There were numerous mobile phones being used for the same purpose. I took a minute or two of footage but resisted the urge to take more because a) it was a serious drain on the battery and b) it could understandably pee off people behind who were trying to watch the performance.

The woman to Hasna’s right was much younger and had a brilliant set of white teeth in her round, attractive, dark-skinned face. She flashed me a smile when she saw me clapping along and I fancy I may have blushed. It didn’t matter because the kettle lamps with the red filters were illuminating everything at that moment. Her clear, sparkling eyes also stood out against the colour of her skin. I had been warned by Sofian and Gilmour of the allure of the eyes of the desert women, about how they could transfix and bewitch you, but I didn’t mind being bewitched tonight. Hasna would look to her to take up the rhythm of each new song with her percussion, be it a tambourine or traditional clapper. It was a bit annoying when, on several occasions, young gentlemen, usually under the influence of alcohol (yes, I saw it being consumed), would decide to ‘perform’ for the rest us right in front of the seated musicians. It never ceased to amaze me how drunk people seem to come to the conclusion that they are both more attractive and more talented whilst under the influence. Well, I suppose I can’t point fingers, but I really I hope I never tried to steal the limelight like these guys thought they could!

When the hour arrived the band made way for DJ HH who had been keeping a rather low profile until now. Cranking up the volume his speakers churned out the latest dance numbers from the world charts, not exactly complementing the sublime music of the desert ladies, but evidently to the enjoyment of most present. I went with it and the four of us did pretty well to let our hair down so to speak. Hasna and her band decided to call it a night at that stage. I had heard that Hasna was known throughout Algeria but I was still quite taken aback by the eagerness of the mob who wanted to be photographed with her and the other women in the band. Eventually they were compelled to depart as one from the tent to escape the melée. Gilmour pounced and managed to nab the nearest of the ladies who obliged us with a token photograph although sadly it wasn’t my desert beauty.

What was apparent to me was that the guys in the tent far outnumbered the girls and those girls who were there were either with family or boyfriends. I remember thinking that Gilmour would have to be the best damn lady charmer south of Algiers if he was going to get a lucky start to the new year. It didn’t happen either for him or any of the other hopefuls there I don’t think because before long it was only a bunch of guys jumping around to the beat. I remember going outside hoping to warm up by the fire. My battery was running low on battery as I tried a few artful photographs on night mode, most of which turned out blurry. Nevertheless, the sky was an inky black canvas on which myriad silvery-white pinpricks of light were liberally sprayed, and beneath it all the darkness of the desert punctuated only by a few fires and lanterns. Those images will live on in my mind beyond the bits and bytes of digital information encoded in the imperfect snap shots.

As I strolled back towards the tent mindful of how damn cold it had become at this early hour I noticed activity at the door of the tent. They were being selective about who could enter (or re-enter) the tent. I was trying to fathom who would be so determined to trek all this way to crash the party when Sofian was suddenly ejected through the entrance flap. Right behind him was the gawky guy with the bad teeth shouting at my good friend and trying to grab him by the arm. Sofian shrugged him off whilst the event employee wagged his finger at him and garbled insults before grabbing a rope to steady his wobbly knees. He was most definitely very drunk. Fortunately for us another one of the event people emerged and gave his inebriated colleague a curt clip round the ear and told him off. He was then the picture of humility, holding up his hands in apology as Sofian and I made our way back under the tent.

Inside Gilmour and Ahmed were still grooving. Sofian, obviously tired, lay down on one of the matresses. The next thing I knew DJ HH was blurting my name out over the loudpeaker: “Welcome to a very special guest tonight, Mr Leo, all the way from England! And to his friend, El Kheyr!” I looked over to Sofian, lying with his eyes closed, oblivious to the fact that his name had just been announced. Gilmour sauntered back from the sound desk grinning. “Did you hear that?”

“Only just” I said. “Not easy to hear anything over this lot,” I said, indicating the dancing groups of guys who seemed to be letting off a lot of pent-up energy. “But I think it was wasted on him,” I said with a smile and glance in Sofian’s direction.

When we got back to the house thirty minutes or so later, courtesy of DJ HH, the door to the front courtyard was locked. Someone raised Jamel on his mobile and he appeared a little while later looking drowsy. He opened up without a word and went straight back to bed. I spied the house owner sleeping in the main bedroom across the hallway when I made my way to the bathroom. I fell gladly onto my sofa bed and plunged into my first slumber of 2014.

I was awake at 8:30 on the first day of the new year; everyone else was fast asleep. Since I knew I couldn’t get back to sleep I got up, donned my shoes, and stepped outside. The street outside was relatively quiet but there were a few people here and there going about their daily routines. A little boy peeped out from a doorway across the road. I smiled at him and he ducked out of view. I decided to be bold and headed for the wadi that lay behind the town and below the prominent ridge I talked of. There was a wide open piece of land I had to cross before I reached the edge of town and the wadi. If you are entertaining visions of a bone-dry valley you would be very wrong indeed. Before my eyes was a surprising vista: to my right, a furrowed field with green shoots emerging from the light-brown soil; behind it, several smaller fields, some barren, some with new growth; to the left another field enclosed by mud walls and with a small homestead abutting it; and further back on either side a proliferation of palm trees. I heard voices from the small house on the edge of the field. Outside there was a fairly new-looking hatchback, a VW Golf or something similar, a notch or two above my VW Polo back in England anyway.

Not being content with only seeing the valley from this angle I decided to cross over to the other side and climb the ridge. This wasn’t as difficult as it may seem from the picture which magnifies the perspective somewhat. The real difficulty was in ascending beyond the stratum of harder rock about two-thirds the way up the ridge. Below it there was a lot of loose rock which could be climbed carefully, but the ridge itself was abrupt, steep and fissured. I decided that I had done enough for my morning amble, took some footage of the landscape, before descending. Interestingly, on my way down I noticed what looked like some fossil corals in some of the sedimentary rock. I’m almost certain that is what they were (my geology degree coming in use here, at long last). Quite a thought to imagine that the arid landscape around me was once inundated by sea.

Back at the ranch an hour later my colleagues were still asleep. Gradually they emerged from their slumber each in turn. After dressing and grooming we collectively made our way back to the main road on foot and crossed to a public tourism centre opposite. A set of imposing wrought iron gates opened onto a paved path which led to large, single-story building. There was a small desk against the wall to the right of the main door on which there were a number of ethnic curios: bangles, rings, charms and so forth. I followed Gilmour and Jamel along an extension of the paved pathway around the building to the left. We arrived at the door to a cafeteria and went inside. We sat at one of several round, stainless steel tables with matching chairs and ordered the usual fare: espresso and crème. A few minutes later the others joined us and in addition to more coffee ordered a batch of pre-wrapped croissants. They were nothing like the fresh variety but we just had to make do.

I noticed, not for the first time, that Gilmour would only take a few sips of his crème before pushing it to one side saying that it didn’t agree with him. He was more of an espresso drinker at this time of day and quite happy to pilfer a cigarette from Oussama or one of the others, although, like me, he professed to only being an ‘occasional’ smoker. Over breakfast Jamel and Oussama asked the rest of us a little bit more about our new year’s party.

“Were people getting drunk?” one of them asked. I looked across to Sofian and let him elaborate on his treatment at the hands of Mr Dodgy Teeth. He didn’t make much of it though. I admitted that some people were consuming alcohol in plain view but I had managed to enjoy myself without indulging (which, surprisingly enough, was true).

“Why do you take issue with drinking anyway when you choose to smoke?” I asked of Jamel and Oussama.

Oussama replied that alcohol was strictly forbidden in Islam and conceded that, strictly speaking, smoking was also haram because of its negative health effects. When I pressed him to elaborate he insisted that alcohol was the worse of the two though. I asked him if it wasn’t possible to drink in moderation and he gave me a sceptical smile.

“In my experience people behave very badly with alcohol,” he replied. I couldn’t really dispute this fact but I did try to make my point that some people were able to drink moderately and could actually control themselves.

“In addition, some alcohol beverages like red wine, actually have some positive side-effects,” I added citing something I had read about red wine reducing heart disease. Oussama raised his eyebrows and said he would have to look into it. All the same I was left with the impression that their views on alcohol were firmly held.

Back outside I took a stroll through the building and out the back with Sofian. There were paving slabs and a couple of smooth cement courts for basketball or football I’m guessing. Evidently there was also on site accommodation. A door to one of the rooms stood open showing a sparsely furnished interior.

“We need more private investment,” Sofian said gesturing towards the accommodation block. “This would not do for foreign tourists.” He had a point if the aim was to attract international visitors to remote destinations like Taghit. Perhaps it’s best to leave these decisions to the local communities? A multi-storied hotel would definitely be an eyesore here, but there was room for tastefully designed bungalows or traditional housing like the hostel in Béni Abbès.

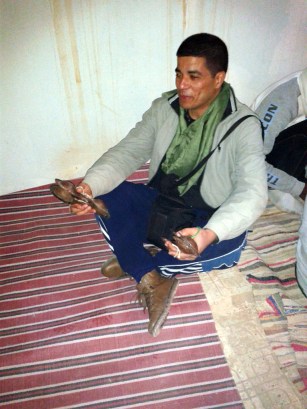

Abutting the northern perimeter was a traditional tent propped up by wooden poles next to which were a couple of more modern, blue canvas-type tents. Sofian suggested they housed curio vendors who would have taken advantage of the influx of tourists over the new year. The display tent was unoccupied. A few rough carpets were spread out on the sand in front of the tent and further forward still was an ornamental fountain (no water) flanked by two stuffed animals that were most certainly wild goats. A bit of online research strongly suggests to me that they are aoudad or Atlas Barbary sheep, a species apparently threatened by poaching and habitat loss. I hope at least one of these two animals had a chance to reproduce before falling prey to the hunter’s rifle. To Sofian’s left and obscured slightly by a thick guy rope is the pelt of a fox with a beautiful thick tail. I never did get to ask the curio seller where he acquired these specimens or what price they commanded.

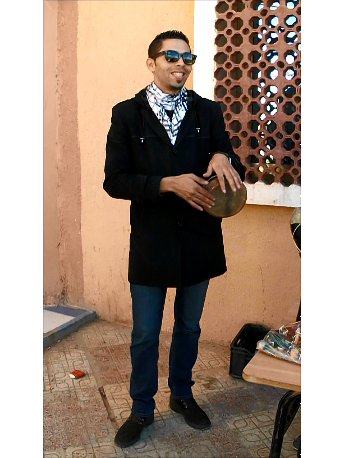

We returned to the main building to find the others sitting on some plastic chairs against one of the walls. There was a fair bit of activity by this time and there were a number of buses and cars parked either outside the gates or just within. Gilmour strolled over to the young boy selling curios and picked up a local drum or debourka. An authentic debourka is covered by a tensioned animal skin just like the traditional drums I knew from Zimbabwe, although I later saw ones with a plastic skin in a northern town which Gilmour claimed had superior acoustic properties. Returning to the present occasion, Gilmour slung the drum over his left shoulder and began rapping the fingers of both hands on the skin in quick succession. It looked effortless but an impressive rhythmic beat emanated from the instrument and reverberated off the nearby walls. I looked over to Ahmed who was smiling and moving to the rhythm. Soon he ambled across and picked up a second debourka and joined Gilmour in a two-part rhythm. And there we had it: music!

After providing us with ten minutes or so of free entertainment it was time to depart. The minibus taxi we had been waiting for had arrived. Besides the six of us there was also the house owner and four others we had met a short while before: a middle-aged woman and her pretty teenage daughter; and her niece and husband, recently married and on honeymoon. We departed and a few minutes later passed through the town centre, busy but not quite as congested as the day before. Once beyond the southern edge of town Gilmour resumed his musical exploits and soon had everyone at the back of the bus singing and clapping to a song they all seemed to know.

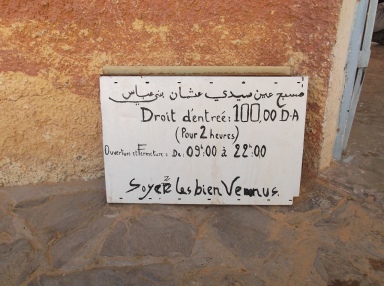

Our journey took us along the same route as the day before but in reverse. We passed the old settlement hemmed in against the road and then the series of dunes that had so impressed me the day before. When we reached the gate we had managed to negotiate the day before there was a protracted negotiation between the driver and a man who was evidently the taker of tolls. Sofian muttered something about extortion but eventually they agreed on a fee per head – 200 DN I think – and we were allowed to pass. We pulled off the road to where a few other vehicles were parked besides a motley collection of curio sellers selling a sample of what was on offer in the marketplace in Taghit: mounted specimens of desert rose; bottles of coloured sand arranged into patterns and desert silhouettes; bangles and bracelets; strips of coloured cloth; some colourful fabric bags (I bought one for 500 DN); and bottles of date syrup and foodstuffs.

The sound of an engine revving alerted me to the arrival of a quad bike manned by some uniformed individuals in sunglasses. They looked like they worked in the tourist trade. I followed the others over to admire the robust contraption. I can’t remember the price for a ride but I do remember Gilmour and Jamel jumping atop the idling machine and posing in turn for Oussama’s camera. I was happy to buy a small paper cup of traditionally-brewed tea from a man in a blue shesh who was kneeling in the sand before a tray and the ashes of a fire.

After having fallen prey to most of the distractions obviously intended for new arrivals we proceeded towards a rocky ridge a hundred yards or so beyond. There were already various groups of tourists wandering amongst the boulders at various levels. The first thing I noticed was the graffiti on the more prominent rocks facing us. Human beings are the same wherever you go in the world; a certain egotistic percentage will always try and leave an indelible sign of their presence at such places. I let my eyes wander over the adjacent rocks not knowing what to look for but hoping that perhaps there might be some paintings akin to the ones made by the bushmen in Zimbabwe, some allegedly thousands of years old. There weren’t any paintings but there were etchings, and some quite impressive ones as well. I posed next to a marvellously stylised image of a lion, my namesake, and a little higher up clambered onto a flat surface to find myself looking down at a very interesting picture.

The etching on this horizontal slab of rock clearly showed a wild goat or sheep (an aoudad?) standing proudly in profile. Around him were various other squiggles and lines etched into the solid, dark-brown sandstone, some forming recognisable images, some not. I could make out an etching of what looked like the sun to one side of the creature. Sofian and the household owner, inconspicuous until now, appeared over the lip of the rock. The latter, reading my mind, elaborated in Arabic the meaning behind the etching and Sofian translated. He explained how the hunters who carved the images had caught the animal and explained the significance of the rising sun to one side of it and the setting sun on the other. He would evidently appear on this rock or perhaps a nearby rock at first light, as if to survey his domain, and again at sunset. This was how the hunters had known when and where to lay in wait for him. Whether or not this was the truth I’m not in a position to say but it sounded plausible. My heart went out to the doomed animal struck down in a moment of solemnity, but it was tinged by admiration for the hunters who seemed to possess an aesthetic appreciation of the fine beast in his desert environment.

From the rock etchings we had turned back towards Taghit, stopping shortly beyond the old settlement of mud houses. I had missed it from the road but the ridge here was strewn with numerous building stones, the ruins most extensive where the slope flattened off. Dropping off to the west there were several large pits and caverns carved into the friable sandstone. Picking our way carefully between the stones Sofian, Ahmed and I climbed to the highest part of the ridge where we had a fabulous view towards the great, sandy erg to the east of us. The edge of the ridge dropped steeply to a moist, palm-covered strip flanking the road into Taghit. Unlike the wadi next to the ridge a little further north, where I had ventured earlier, surface water was visible here, although it probably flowed continuously after a decent rainfall.

It was mid-afternoon by the time we made our way back down to the minibus. The others were waiting impatiently for us. Gilmour informed us that we had ‘missed out’ on some Cuban beauties who they had met after we wandered off to see what lay higher up. He later showed us several snaps he had taken with the ladies in question, grinning happily all the while. He resumed his conversation with the middle-aged Algerian woman, leaning across at one point to tell me that she had extended an invitation to me to visit her in Tipaza before I headed back to England, yet another example of the warmth and friendliness of the Algerian people. Back in town we disembarked and paid our driver his dues and set about looking for something to eat. Gilmour remained with the ladies at what passed for an upmarket café in Taghit, whilst Sofian and I sought out something cheaper at our ever-dependable Pizzeria-cum-‘Fasfood’ establishment. Ahmed and the other two teachers joined us at some point deciding that the burgers were a bit expensive at the other place.

When Gilmour caught up with us he informed us that we had all been invited to a party with our friends that evening. Oussama and Jamel expressed an interest so I assume they did not anticipate any drunkenness. Sofian was non-committal so when the opportunity presented itself I asked him in private what his thoughts on the matter were.

“Those guys are just interested in the girls,” he replied. Well yes, I’m pretty sure that was the case I thought to myself, but what of it? “Anyway, I don’t feel like going out tonight. I think I will just relax back at the house.”

To be honest it was quite a relief to hear him echo my own sentiments. After the late night and early rise I wasn’t sure I was up for another party. The other thing was my rapidly dwindling supply of dinar. Sofian had assured me that he could draw money from his post office account and settle any shortfalls but I didn’t want to put pressure on him if I could help it.

We ambled across towards the dunes stopping at a curio shop where Ahmed showed me a set of woven couscous pots.

When I suggested that we climb the dunes again for one last sunset in the desert it wasn’t met with the most enthusiastic response from the others, with the exception of Sofian. There was no way I was going to miss out on my final evening in the desert so Sofian and I made for the same dune that we had climbed the day before on the understanding that the others could follow, wait for us or go back to the house; the choice was theirs. I looked back after Sofian and I had climbed for a few minutes and saw Jamel, Oussama, Ahmed and Gilmour trudging slowly up the ridge between the dunes. We had probably been up top for ten minutes by the time Ahmed finally made it, panting and gasping for air. We had a bit more time before sundown than the previous evening and there weren’t quite so many people to contend with. I was sporting a red shesh I had bought from a stall near the taxi terminus. Despite earlier reservations spirits soon lifted and before long Oussama was shooting away with his precious Nikon while the rest of us adopted various poses: smiling; serious; looking towards the horizon; leaping in the air in unison. It was a good way to end our desert adventure and probably three days together which none of us would ever forget.